Archived Content

In an effort to keep CISA.gov current, the archive contains outdated information that may not reflect current policy or programs.Torrential Flooding

Flood: any high flow, overflow, or inundation by water that causes or threatens damage.

Flash Flood: occur in small and steep watersheds and waterways and can be caused by short-duration intense precipitation, dam or levee failure, or collapse of debris and ice jams. Most flood-related deaths in the U.S. are associated with flash floods.

- Flash floods are described as flooding that begins within 6 hours, and often within 3 hours, of heavy rainfall (or other cause). Flash floods can be caused by several things but is most often due to extremely heavy rainfall from thunderstorms.

Urban Flooding: can be caused by short-duration, very heavy precipitation. Urbanization creates large areas of impervious surfaces (such as roads, pavement, parking lots, and buildings). The increase in immediate runoff combined with heavy downpours can exceed the capacity of storm drains and cause urban flooding.

River Flooding: occurs when surface water drained from a watershed into a stream or a river exceeds channel capacity, overflows the banks, and inundates adjacent low-lying areas. Riverine flooding depends on precipitation as well as many other factors, such as existing soil moisture conditions and snowmelt.

Coastal Flooding: is predominantly caused by storm surges that accompany hurricanes and other storms that push large seawater domes toward the shore. Storm surge can cause deaths, widespread infrastructure damage, and severe beach erosion. Storm-related rainfall can also cause inland flooding and is responsible for more than half of the deaths associated with tropical storms. Extreme weather affects coastal flooding through sea level rise, storm surge, and increases in heavy rainfall during storms.

For floods that cost over $1 billion, the average total of damages is $4.7 billion per event. Over the past 20 years the U.S. has reported 4x the amount of billion-dollar flood disasters compared to 1980-2000.

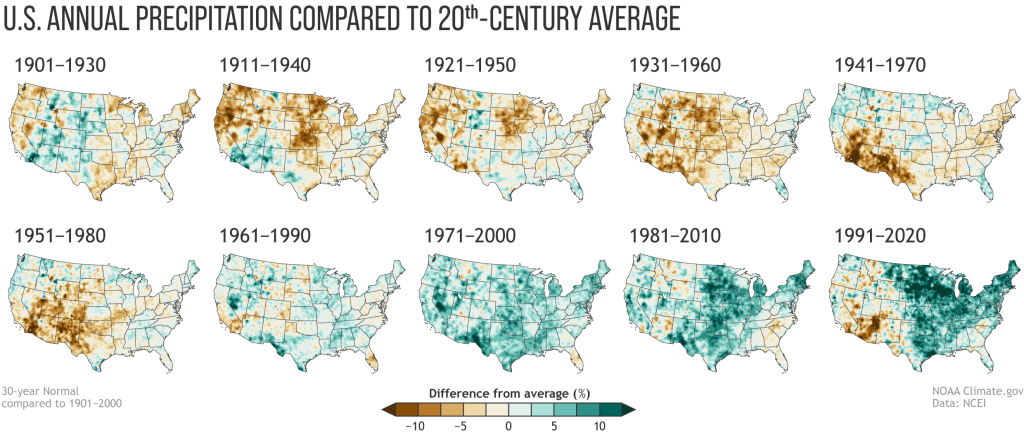

Flash flooding has increased by more than 10% in the Southwest accounting for the greatest increase in sudden onsets on heightened rainfall totals among hot spots, while storms in the Northeast are generating about 27% more moisture than a century ago. New research has shown that, as the baseline temperature annually increases, flooding events will become 8% “flashier” by the end of the century. This means that increasing temperatures make more moisture available, which continues to drive amplified storm rain totals.

With the shift in stability of weather systems, the shift in location and timing of rainfall events will present unique hazards to all critical infrastructure sectors with minimal notice for preparation during a developing event.

CISA’s Role in Increasing Flood Resiliency

CISA continues to be a major purveyor of data provided by interagency partners to stakeholders across the nation through webinars on increasing threats from atmospheric heating amplifying moisture content within storm events.

CISA produced a document titled Sources for Resilient Solutions to relay lessons learned from seven small- to medium-sized utilities nationwide that have responded to extreme events, such as damaging floods.

Critical Infrastructure Impacts

Just one inch of floodwater can cause up to $25,000 in damage according to FEMA. 12 inches of flowing water can lift and carry away most vehicles, presenting a secondary threat to infrastructure in large floating debris.

Large floods can damage roadways, bridges, energy equipment, residential properties, agricultural sites, intake pipes, water infrastructure, and most physical infrastructure as soil erosion, debris flows, mud slides, rockslides, river flooding, and rapid wash flows present secondary threats made possible by increased precipitation. The damage from a single flood can last multiple seasons if the soil health is strongly affected by debris, contaminated water, higher levels of toxins or chloride, or by stripping nutrient filled topsoil.

- Pipelines and above and below the surface could be damaged by changing soil conditions causing pipes to bend and shift and rapid erosion exposing infrastructure to debris damage.

- Most commercial power facilities are located near natural waterways for cooling and have associated increased flood risks as heavier rainfall events result in more runoff.

- The World Wildlife Foundation (WWF) states by 2050, 1 in 5 existing hydropower dams will be in high flood risk areas, up from the current rate of 1 in 25 hydropower dams.

- Energy equipment in the direct path of water flow is subject to catastrophic damage due to debris and speed of water flow. Rising water can cause damage to control circuits and distribution panels.

- Flooding on farmlands can cause crop loss, contamination, soil erosion, equipment loss, debris deposition, and the spread of invasive species.

- Compounding threats with increased rates of drought-triggered subsidence can result in unexpected water pooling in areas which have become the low-lying elevation.

- Nearly ¼ of U.S. critical infrastructure is at risk of flooding that would render them unusable. This percentage is expected to grow as extreme weather continues. (US News, https://www.usnews.com/news/national-news/articles/2021-10-11/flooding-threatens-25-of-us-infrastructure-study-says)

- Drinking water and wastewater systems are at risk of damage and contamination from flooding especially because they are often located near bodies of water for supply or discharge.

Torrential Flooding Resources and Training

Learn more about the impact torrential flooding has on critical infrastructure and how extreme weather affects the likelihood and severity of floods.

Fifth National Climate Assessment: Extreme Events Are Becoming More Frequent and Severe

The Fifth National Climate Assessment discusses how the risk of extreme rainfall has changed in the past 100 years.

Floods | Ready.gov

Learn how to stay safe before, during, and after a flood.

Flood Safety Tips and Resources (weather.gov)

Learn about flood safety, different types of flood warnings, and find other NOAA resources.

Flood Maps | FEMA.gov

Learn how to access and use flood maps to determine if a particular location is at risk of flooding.

USGS Flood Information | U.S. Geological Survey

Examine current flood conditions based on U.S.G.S. system of streamgages.

Communicating Potential Flash Flood & Debris Flow Threats

Understand the connection between wildfires, flash floods, and debris flow events and providing decision-support to stakeholders based on their needs.